Commemorating 75 Years of the UDHR: Advancing Health Justice in a Turbulent World Symposium

By Bertina Lou

OTTAWA, ONTARIO

DECEMBER 2023

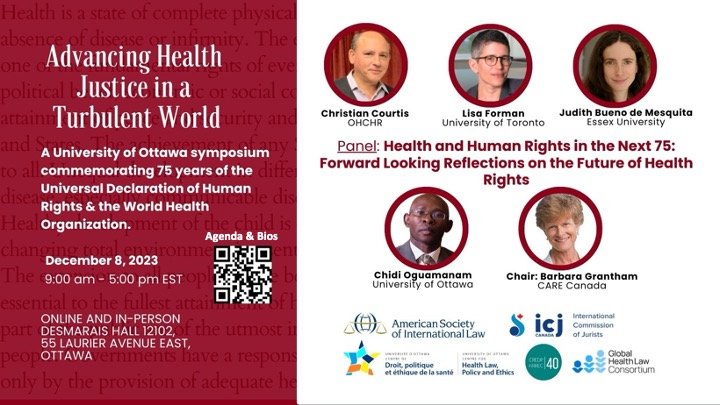

On December 8, 2023, the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was commemorated at the Advancing Health Justice in a Turbulent World Symposium at the University of Ottawa. Hosted by the uOttawa Centre for Health Law, Policy and Ethics, the International Commission of Jurists, the Human Rights Research and Education Centre, the Global Health Law Consortium and the American Society of International Law, this event featured experts from institutions worldwide to facilitate reflections and discussion on a revitalized approach to tackling interconnected global health challenges through rights-based approaches.

As the COVID-19 pandemic pushed the human rights implications of public health crises to the forefront of international law, the World Health Organization (WHO) worked to conclude negotiations towards a Pandemic Agreement, an international instrument on pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response. Participants at the symposium examined the Pandemic Agreement’s shortcomings in relation to a rights-based approach to health and considered how human rights frameworks can drive future reforms to pandemic-related international law.

Open AIR co-founder Chidi Oguamanam presented during the closing panel “Health and Human Rights in the Next 75: Forward-Looking Reflections on the Future of Health Rights” along with panelists Christian Courtis (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights), Lisa Forman (University of Toronto), Judith Bueno de Mesquita (Essex University) and panel chair Barbara Grantham (CARE Canada).

Left to right: Judith Bueno de Mesquita, Chidi Oguamanam, Lisa Forman, and Barbara Grantham

LOOKING INTO HISTORY

Chidi Oguamanam situated the advancement of global health justice alongside the evolution of human rights, especially those of marginalized groups. Despite global recognition of Article 25(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, both of which describe physical and mental health as fundamental rights, there remain differences in formal and substantive equality for marginalized populations that hinder access to health justice.

Indigenous Peoples in particular experience disparities in nearly all social determinants of health, with few significant improvements 75 years after the UDHR. Given that health disparities are rights violations in essence, it is imperative to change the narrative.

The International Labour Organization (ILO)’s Convention 169 was the first comprehensive international attempt to address the rights of Indigenous Peoples (including health) in a labour context. It was followed nearly two decades later by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, in which Article 24 describes Indigenous Peoples’ rights to maintain their traditional health practices as well as access mainstream health services. This document entrenched Indigenous Peoples’ health as an issue for the United Nations and has since given rise to specialized organizations focusing on Indigenous Peoples’ rights around the world, inspiring other human rights instruments. In Canada, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) found in a landmark 2016 decision that the Canadian government discriminated against First Nations children in the area of child welfare services.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

For consideration as part of the development of a global health framework based on human rights, Oguamanam raised the following three concerns:

National accountability so that domestic policy entails reporting mechanisms, permits court litigation and advocacy, and rethinks data and research ethics.

New technologies and data to account for how generative artificial intelligence, the environment, food agriculture, and the life sciences intersect with the social determinants of health in order for technology to be recognized as a ground of discrimination for human rights claims.

A deliberate approach to knowledge governance that supports Indigenous epistemologies in their cultural context of knowledge production, traditional medicine and health practices.

Moving forward, the Pandemic Agreement (and any strategy based on a human rights approach to health) should address these considerations.

The international health order, as it exists, does not protect the most vulnerable populations. A solution worth exploring is the implementation of one cohesive global strategy with a “no boundaries” approach.

May the future of health rights be rooted in a global health framework where the inherent dignity and the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family are fully enjoyed.

View select session recordings on the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Law, Common Law Section YouTube Channel under the “Conference” playlist.